Fear and Loathing of Quarantine – Notes from the Plague days

A tiny beast has changed the world. This microscopic entity named after the gigantic burning star, who’s name I will not take, with its pathetically small string of genetic material has created havoc in the way we live and die across the earth. Everything started with a mutation in one of the beast’s molecules, so it was able to attach to our respiratory tract. From there on, the proverbial butterfly flapped its wings and shutdown airports, industries, colleges, changed the levels of air pollution level (for good), increased domestic violence, increased sales of sex toys, cancelled free hugs at parks, closed ozone holes, made us bang pots and pans and of course, killed way too many people.

Facing a beast of this level of notoriety, it’s surprising how low-tech the preventive strategy is; some rubbing alcohol, badly sewn cloth mask, 20-second hand wash with soap and not sneezing in another’s face. But, there is also this medieval invention called “quarantine”, along with its stern-faced cousin “lockdown” and the misnamed “social distancing” (what we really need to do is physical distancing).

Now that we are almost in the second month of isolation, feeling dull, anxious, and unmotivated, it’s time to look at the history of quarantine. The first-ever documented western response to a disease with isolation was in 1377 at the seaport of Ragusa of the Venetian Republic (now, Dubrovnik in Croatia). Ships docking in the port had to go through a 30-day isolation period and a 40-day period for inland travellers. This was a response to the periodic bubonic plague outbreaks.

The word quarantine is derived from the Italian word “quarantenaria” which means “forty days”. It is not really known why 40 days was decided; it could have been inspired by Pythogoras’ theory of numbers where the number 4 had special significance, or it could have been because Jesus walked around the desert for 40 days.

The Venetians also built the first quarantine centre on an island near the city of Venice in 1423. This model was quickly followed by other European states as the most favoured method of dealing with plague outbreaks. Other diseases also used this treatment model – “lazar houses” for leprosy, “sanatoriums” for TB and “asylums” for mentally ill people.

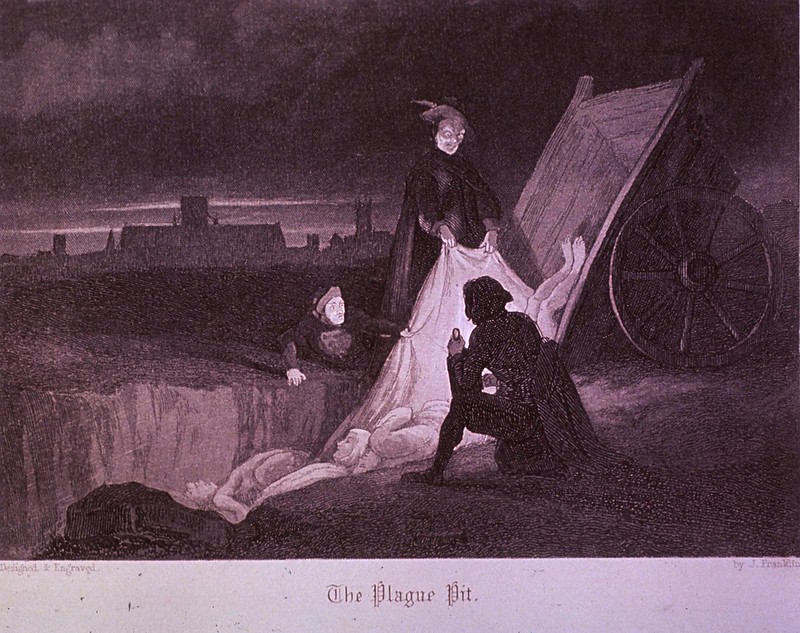

Seventeenth-century London, like any city of the time, also had periodic outbreaks of the plague and the government implemented quarantine strictly. A health inspector would identify the house where someone had died of the plague and would padlock and seal the door with the inhabitants inside. The door would be marked with a red cross and inscribed with the words ”Lord may have mercy upon us”. There would also be a watchman posted outside so the residents did not venture out and no one visited them except the government officials. Another way to quarantine the infected was to house them in government-built “pest houses” where they were supposed to recuperate in hygienic and healthy conditions. But, judging by the nickname given by the public, I am sure it was a miserable place to live.

The effectiveness of the quarantine was mixed, mostly because they did not know the causal agent of the plague, incubation times or how it spread. They did not have a way to screen asymptomatic carriers, so despite many restrictions like a wall around Marseille in 1720, thousands died. Sometimes, quarantine exacerbated the situation when whole families were locked into a house, healthy people were also locked with plague – infested relatives and lived with infested rats and mosquitoes increasing their chances of getting the disease.

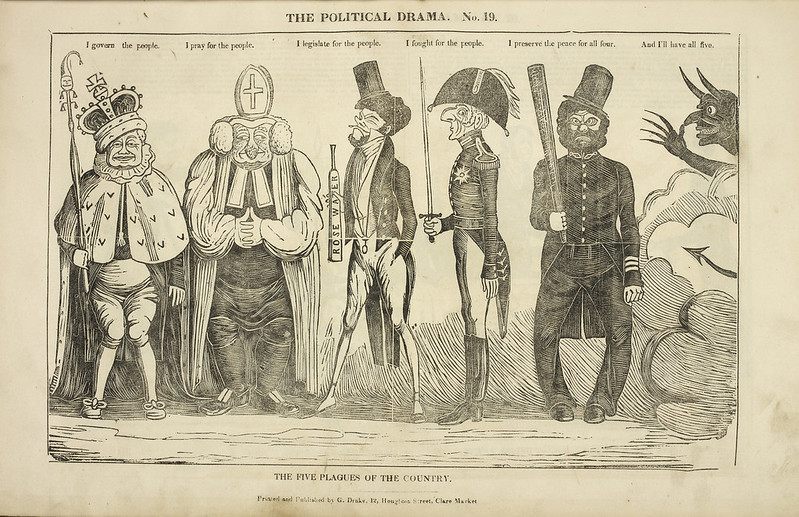

In the 1675 plague outbreak, the main reason why people revolted against the government quarantine was due to the economic woes faced by the poor. The middle class who had to work for a living were most affected. Professions like coachmakers, fishmongers, tailors and innholders were the most affected. Although common perception was that the plague was “morally indifferent” meaning it can infect anyone from rich to poor, man and woman, healthy and the weak, the quarantine implementation was not classless. The rich immediately migrated into the countryside. A popular saying at that time was “flee far, flee speedily, return slowly”. But the poor could not afford this. The rich also bribed the inspectors to lie and hide information about plague deaths of their family members. They also hid their servants who showed symptoms out of the public eye.

Another reason was the violent and sometimes arbitrary enforcement of this law, which resembled punishment. Sometimes when people did not agree to be quarantined,it was forcibly enforced. Even people who were caught sitting in the doorway of their quarantined houses were shut up. Sometimes, the punishment for returning to a previously quarantined house before proper airing was to shut them up in quarantine. In some cases, whole neighborhoods were quarantined quite arbitrarily.

The populace believed that the plague was divine punishment. They also made an association of the plague with “filth”, both material and social. They accused the “dirty” communities (prisoners, prostitutes, jews, catalans, immigrants etc ) of causing and spreading the disease. The sick were not looked as victims, but as carriers of a curse given by god. With large crosses marked on the doors of the victim’s house, increasing the sense of victimhood, it was only natural that people broke the rules of quarantine.

But local authorities were reluctant to abandon their strategy as they feared unrest and chaos on the street. During the 1665 plague attack of London, there were many pamphlets and books arguing that quarantine was a bad thing.

Coming back to the present Covid-19 infection in 2020, we have also seen some resistance to isolation and quarantine. The reasons are not because of religious dogma (although there are some examples). People’s trust in modern medicine and biomedical research is still high as the voices calling for absurd claims like cow urine, ginger, clorox etc have fallen by the wayside and the world is suddenly interested in the nuances of RT PCR, adjuvants, vaccines and clinical trials. Most of the misinformation is an overenthusiastic misinterpretation of the scientific process by habitual self-aggrandizing chest thumpers (Donot Trump, Melon Musk, Didier Dumbo). There is, of course, the side project on national pride with Ayurveda, homoeopathy and natural herbs (none of which has been shown to work ).

However, what continues from the times of medieval plague to now is that economic disparity influences one’s experience of quarantine. The rich are able to live without work for months, but workers who depend on daily wages and live in the margins of society without a security blanket are severely affected. The most vulnerable are the poor in urban areas in crowded housing, poor sanitation, low income and no access to health care. The police highhandedness is also reserved for the lower income and marginalized groups.

But, this beast is no plague. With a 4% mortality rate, it’s mild compared to Nipah Virus or Kyasanur Forest Disease Virus, which are much scarier zoonotic viral diseases. But, the question is, will we learn from this beast to deal with the next one? Will we think about making behavioural interventions like quarantine and isolation more effective?

2 Comments

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

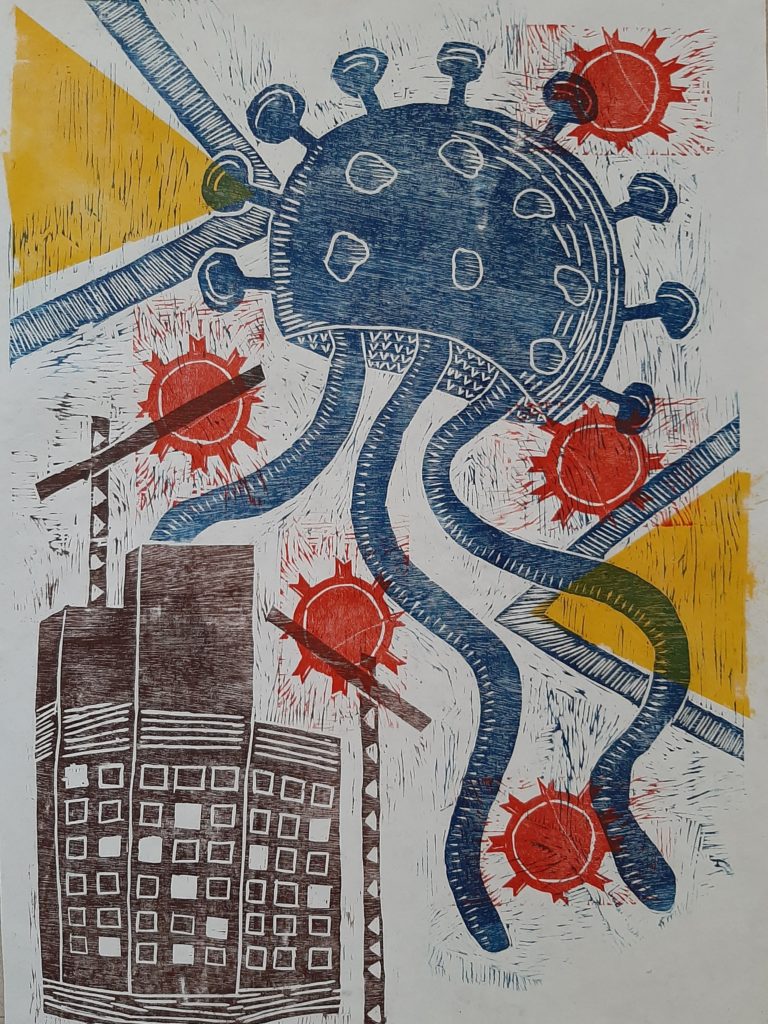

I am intrigued by the poster that you have made depicting corona virus.

Thanks! Its a woodcut print